LUNAR NEW YEAR FAIR or 新(Xīn)年(Nián)庙(Miào)会(Huì)

2022 Mini Temple Fair inside Union Market DC

History of Lunar New Year Temple Fair

People tend to associate Temple Fair in China with the Chinese New Year. Indeed, at this time of the year, the temple fair is a depository of the scents of Lunar New Year: once stepping into the market, you’ll be immersed in the emblematic poppy red. However, temple fairs are not exclusive to the season of Lunar New Year.

[Figure 1] The Entrance to the Temple Fair at the Temple of Earth, Beijing, Lunar New Year 2018. This has been the most popular Lunar New Year temple fairs in Beijing.

The gathering of vendors and entertainers around a specific worship place began from Tang Dynasty (618–907) when Buddhism in China developed more accessible patterns of preaching to win believers from the indigenous Taoism, such as the vernacular narrative and performance of sutra stories. The Buddhist temples, therefore, provided a stage for folk art performance troupes and individual artists. These activities attracted thousands of audiences, and the merchants certainly made the most of it. As the performances were held regularly according to Buddhist festivals, the fairs took place at or around the temples following the same schedule. With the boost of the market economy and the monetary innovation (i.e., paper money) in the Song Dynasty, Temple Fair claimed a more significant role in the leisure time of ordinary people. In addition to the intermingling of Buddhism with folk religions through the centuries, Temple Fair in ancient China further flourished thanks to the sophisticating of the polytheistic folk religion system under the rulers’ encouragement which led to the mushrooming of temples in the Ming and the Qing.

As temples are places of worship, attendants of these temple fairs were first and foremost believers and followers of the enshrined deities. Nevertheless, the logic behind the trio function (religious-cultural-economic) of urban and rural temple fairs were different. Magnetic temples in cities and towns would be the site of major religious activities. The adorers — some making a wish, others making a grateful revisit as their wish came true — would bring incense and joss papers. The local and nearby merchants, therefore, would gather around and provide religious goods, food and flowers offering to gods, as well as snacks and tea for the visitors to satisfy their hunger and thirst. In this way, the busiest temple fairs took place at the sanctuaries whose deities enjoyed the most popularity and highest worship among the local population, for example, City God Temple (城隍廟), God of Earth Temple (土地廟, not to be confused with the Temple of Earth), Temple of Emperor Guan (關帝廟, dedicated to the historical general Guan Yu 關羽)、Dongyue Temple (東嶽廟, Temple of Mount Tai, dedicated to the Great Deity of the Eastern Peak) and the related Temple of Bixia Yuanjun (碧霞元君廟, dedicated to the Lady of Mount Tai), Temple of the King of Pharmaceuticals (藥王廟), etc.

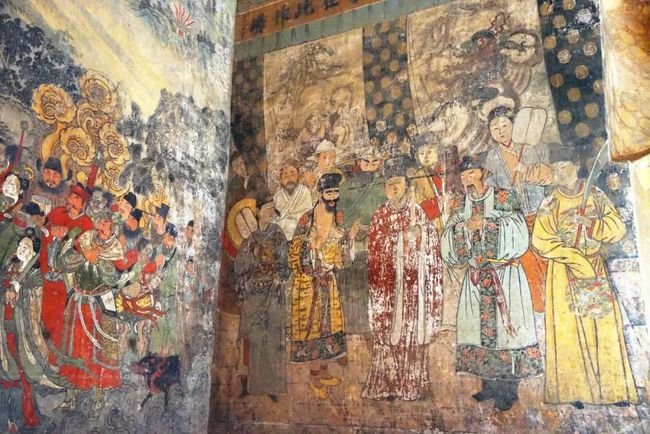

[Figure 2] Mural (c. 1324), originally housed in the main hall of the God of the Huo Spring Temple (霍泉水神廟, next to the well-known Guangsheng Temple [廣勝寺] in today’s Shanxi Province).

The consecutive murals in this hall tell the course of the worship of God of the Huo Spring: praying to him for rain on his birthday, the dragon king distributes rainfall, and people’s performance of music and dance to thank the god. [Figure 2] Mural (c. 1324), originally housed in the main hall of the God of the Huo Spring Temple (霍泉水神廟, next to the well-known Guangsheng Temple [廣勝寺] in today’s Shanxi Province). In this picture, the partial mural on the left wall is the worship scene, and the other part in front of you depicts a scene of a troupe about to play “miscellaneous music” (散樂, a type of singing and dancing performance in the Yuan Dynasty. Chinese Title: 「大行散樂忠都秀在此作場圖」). The left one (south wall) depicts the scene of worshipping the god of rain on his birthday,

By contrast, in the countryside where influential sanctuaries were absent, people would please the gods and the immortals by performing operas and setting up feasts, thus entertaining themselves in turn. As cultural life in rural areas was not comparable to that in cities and towns where opera halls and tea houses dotted, this explains the presence of a pavilion-styled performing stage to the opposite of the main hall as a common layout of humble rural temples. Similarly, on the one hand, rural temple fairs constituted compensation for the underdevelopment of local market places: most of the goods there were for daily use. On the other hand, urban citizens were looking for something exciting and unusual. Such mentality persists to the present day: surrounded by modern, industrial and standardised stuff, traditional, artisan and unique products successfully cater to the preference of today’s city dwellers — Look at those handmade crafts and freshly made street food, the carriers of fading, intangible traditions at Lunar New Year temple fairs! Is it redolent of the Christmas market?

Wherever the temple fairs took place, in traditional Chinese society, temple fair was one of the very few occasions customised to the natural need of entertainment when people were allowed to eat and drink to their hearts’ content which was usually advised against according to Confucian ethical concepts. Indeed, besides “gluttony,” all sensory pleasures (“human desires,” 人欲) were viewed as the opposite of the heavenly rationale (“天理”) in the view of official ideology after Song Dynasty. Social strata were broken down, and pretentious etiquettes were violated temporarily: dressed-up grassroots mimicking the lords in the procession, male and female audience mingling in the crowd. A carnival spirit was instilled in the routinely ritual event. The folk temples, therefore, have developed into a community space, an assemblage of rituals, daily life, and economic activities. In other words, temple fair has been taken as a public occasion for relax, entertainment, assembly, and then for exchange of goods, arguably an ancient Chinese counterpart of medieval European church square market. As a late-Qing inscription reads, “Our ancestors were not Buddhists. Why do we establish this (temple)? To follow the custom, to fulfil the will of the commons. The fellow countrymen are working hard all year round without rest. Once coming across a temple court, they arrange food and drinks, summon guests and friends and enjoy the hustle and bustle, as if the spirit of Community Days of Spring and Summer passed down … Since there are no temples nearby, our countrymen petitioned for the construction of the temple.”

Blog prepared and edited by Yuxuan Cai

History Ph.D Candidate at University of Cambridge